Gold Star Spouses Describe Pain of Losing Bereavement Benefits in Remarriage

6 min read

For Gold Star spouses, the pain of losing their husbands in the line of duty can be almost unbearable.

But sometimes, after widows and widowers of fallen service members have grieved and moved forward with their lives to find love again, they find themselves facing a difficult choice: whether to marry and lose the survivor benefits the government granted them to compensate for the loss of their spouses.

Gold Star spouses now lose their Survivor Benefit Plan, or SBP, benefits if they remarry before turning 55, as well as their Dependency and Indemnity Compensation benefits if they remarry before 57.

Last month, two veterans in Congress, Reps. Seth Moulton, D-Mass., and Michael Waltz, R-Fla., introduced a bill — the Captain James C. Edge Gold Star Spouse Equity Act — that would remove these age limits.

In interviews with Military.com, spouses whose husbands died in the line of duty described the pain the risk of losing their survivor benefits causes them.

“My husband fought for our country twice, and he died because of it,” said Gold Star wife Aimee Wriglesworth, whose husband died of melanoma in 2013 caused by exposure to burn pits in Iraq. “He’s the one … who did all those things for those benefits. But … I was his caregiver for a year. And taking that away, if I choose to get married again, takes away everything I did as well. It says that all the things I did as a military spouse don’t matter. And I feel that is a big deal.”

The SBP pays the surviving spouse of a service member who dies on active duty 55% of what the service member’s retirement pay would have been, if he or she had retired at 100% disability at the time of death. The Dependency and Indemnity Compensation benefit pays $1,357.56 each month to eligible survivors of active-duty service members who died in the line of duty, and survivors of veterans whose deaths are deemed service-related.

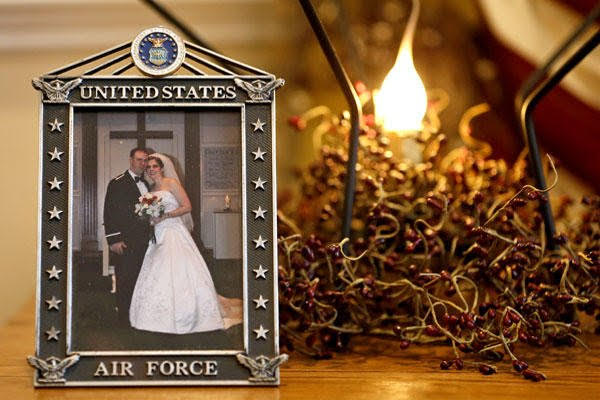

Wriglesworth began dating her late husband, Army Maj. Chad Wriglesworth, when she was 18. She fell in love with his kindness and dry sense of humor, she said. They married on her 20th birthday and soon had a daughter named Savannah.

Chad Wriglesworth deployed to Joint Base Balad in Iraq in 2008 and 2009, and to Afghanistan in 2011 and 2012. He received the Bronze Star and Combat Action Badge during his Afghanistan deployment.

But he also developed melanoma, which Wriglesworth said was confirmed to have been caused by the burn pits he was exposed to in Iraq. His Nov. 20, 2013, death is officially listed as having occurred in the line of duty, she said.

Not only had she, at 27, lost the man she had known almost her entire life. But Savannah — at the time, just two weeks away from turning five — had also lost the father who doted on her, who she snuggled with on his hospital bed and during his treatments, and didn’t flinch from when he lost his hair and started looking sicker.

“And that’s still the hardest thing today,” Wriglesworth, her voice breaking, said in an interview. “I miss him, but what it took from my kid is the worst thing. It altered her life in a way that can’t be fixed.”

Moving Forward

But she pushed through that pain and continued living her life. When Chad was dying, he told his wife he wanted her to be happy after he was gone, and to find a partner who would be a good role model for Savannah.

She found exactly that in her now-fiancé, Mike Brewer, whom she met a little more than a year after her husband’s death.

Mike was also in the Army and lost friends of his own in battle, she said, so he understands what Chad’s memory means to her and Savannah. He wears his dress uniform to visit Chad’s grave with the Wriglesworths, and sits down with Savannah to watch videos of her late father, so she remembers her dad.

Savannah even calls Brewer “bonus dad,” Wriglesworth said.

But though she longs to marry Mike, the loss of benefits that would come with that would upend their lives — and jeopardize the steps they’ve taken to heal since Chad’s death.

Wriglesworth worked as an EMT until her husband’s 2013 death, after which she went back to school to become a social worker. Her survivor benefits pay for her schooling but would go away if she remarried now.

Savannah receives Social Security benefits, but those alone wouldn’t be enough to pay for everything she needs, Wriglesworth said.

“Life shouldn’t be about money, but let’s be honest: Money is what allows me to put clothes on my kid’s back and feed her and make sure she lives in a good neighborhood and [goes] to a good school and [has] good quality child care,” Wriglesworth said.

Wriglesworth also has a medical condition that Tricare now covers, but if she lost those benefits, her treatments would become very expensive. Her fiancé’s insurance would not cover her condition as well as Tricare does if they got married.

The benefits also make it easier for both Wriglesworth and her daughter to go to therapy to deal with the pain of losing Chad. As Savannah neared middle school age, Wriglesworth said, the weight of her loss started to hit her, and she needed to talk to a therapist about it.

And, Wriglesworth said, getting remarried wouldn’t erase her own depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress she has suffered since losing her husband and for which she requires treatment.

“No amount of money makes this not hurt,” Wriglesworth said. “But it helps a lot to be able to take my daughter to therapy or to be able to take myself to therapy, and have insurance to cover that. It helps a lot to know that I can go to school to better my life. And that security is something I feel my husband gave me, because my whole world was taken from me when he died. Everything.”

‘Absolutely Devastating’

Emily Feeks, who lost her Navy SEAL husband, Special Warfare Operator 1st Class Patrick Feeks, in the August 2012 crash of a Black Hawk helicopter in Afghanistan during a firefight with insurgents, is also facing the choice of whether to give up benefits in order to get married.

Feeks remembers her late husband as kind, jovial and larger than life. He had wanted to become a SEAL since he was eight years old and got LASIK surgery to make that dream a reality.

Her husband’s death was “absolutely devastating,” she said.

“You have this world with someone, and you have this plan,” she explained. “And everything was destroyed in one second.”

Feeks was also in the Navy when she and Patrick met at Naval Amphibious Base Coronado, California, in 2010, right after she returned from Afghanistan and he got back from Iraq. She stayed in the service for eight more years after Patrick’s death so she could retire with full benefits.

Feeks is planning to get remarried in October. She’ll keep the benefits she earned from her own service, but is prepared to lose the indemnity pay she has received since Patrick’s death.

“People that have never been in our place tend to say things [like], ‘You should lose that [survivor benefits] when you get remarried; it should be your new husband’s [or spouse’s] responsibility,'” Feeks said. “That’s not how that should work. That doesn’t negate that that person has lost their life for this nation.”

As for Wriglesworth, it will probably be several more years before she can get remarried. She said she will likely wait until she’s finished her master’s degree, found a good job and Savannah has gone off to college, so when the benefits go away it won’t be as much of a blow.

But now, because Aimee and Mike live together in Texas but aren’t married, she said, “I feel judged all the time” by people who don’t understand her situation and reach their own conclusions.

“It’s hard to go to church,” Wriglesworth said. “How do you explain that to people? On top of being a widow — people actually respect that. They go, ‘Oh wow, you’re a widow. Thank you for your sacrifice.’ And then, ‘Oh, but you’re not married.'”

Wriglesworth hopes Congress passes the law to repeal the age limits on remarriage, so she can live her life the way she wants.

“I still carry my husband with me,” she said. “It doesn’t mean that I’m not a Gold Star widow, if I love somebody else as well. … No person, man or woman, should have to answer for getting married.”