Military Throwing Cash at Recruiting Crisis as Troops Head for the Exits

10 min read

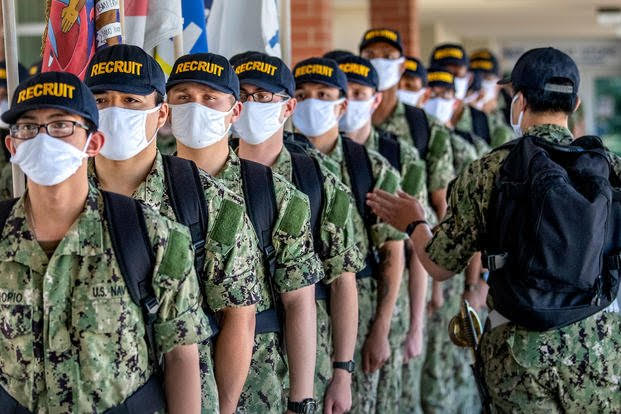

A recruit chief petty officer does a mass count of his division as they prepare to march in formation at Recruit Training Command

Hints that the armed services might soon face a problem keeping their ranks full began quietly, with officials spending the last decade warning that a dwindling slice of the American public could serve.

Only about one-quarter of young Americans are even eligible for service these days, a shrinking pool limited by an increasing number of potential recruits who are overweight or are screened out due to minor criminal infractions, including the use of recreational drugs such as marijuana.

But what had been a slow-moving trend is reaching crisis levels, as a highly competitive job market converges with a mass of troops leaving as the coronavirus pandemic subsides, alarming military planners.

“Not two years into a pandemic, and we have warning lights flashing,” Maj. Gen. Ed Thomas, the Air Force Recruiting Service commander, wrote in a memo — leaked in January — about the headwinds his team faces.

For now, the services are leaning on record-level enlistment and retention bonuses meant to attract and keep America’s military staffed and ready — bonuses that continue to climb.

In an interview with Military.com last month, Thomas didn’t mince words. He knows he is competing against the private sector to hire people, from technology giants to regional gas stations.

“If you want to work at Buc-ee’s along I-35 in Texas, you can do it for [a] $25-an-hour starting salary,” Thomas said. “You can start at Target for $29 an hour with educational benefits. So you start looking at the competition: Starbucks, Google, Amazon. The battle for talent amidst this current labor shortage is intense.”

Paired with those competitive offers for workers are a large number of service members retiring, some having delayed leaving the ranks during a pandemic that saw huge instability in the job market.

Since fiscal 2020, the U.S. Department of Labor’s Veterans’ Employment and Training Service — known as VETS — has anticipated that around 150,000 service members would transition out of the military annually as part of its budget justification documents.

But in 2020, the Transition Assistance Program, or TAP, the congressionally mandated classes that prepare troops for life outside the military, helped counsel 193,968 service members on their way out of the military, said Lisa Lawrence, a Pentagon spokesperson. That’s nearly one-third more newly minted veterans than the Labor Department had planned for.

In 2021, that number grew to 196,413. Prior to 2020, the Department of Defense did not report the total number of TAP-eligible service members transitioning, although Lawrence said the number has been somewhere between 190,000 and 200,000 annually in recent years.

Payouts aimed at attracting new service members to replace those outgoing veterans are at all-time highs. The Army started offering recruiting bonuses of up to $50,000 in January, and last month the Air Force began promoting up to $50,000 — the most it can legally offer — for certain career fields.

The Navy followed with its offer of $25,000 to those willing to ship out in a matter of weeks. It says the bonuses are the result of an “unprecedentedly competitive job market.”

Cmdr. Dave Benham, a spokesman for the sea service’s recruiting command, told Military.com in a recent phone interview that “the private sector is doing things we haven’t seen them do before to try and attract talent, so we have to stay competitive.”

Benham said the scope of the Navy’s offer — a minimum of $25,000 to ship out before June — has “never happened before to anybody’s collective knowledge around here.”

Courting and Paying for Talent

The pandemic economy has placed private-sector workers in the driver’s seat, pushing employers to offer more lucrative incentives such as better benefits, flexible work-from-home schedules or massive signing bonuses to make hires. That is putting major pressure on the military as it tries to attract recruits who may be considering the civilian job market.

It’s all been complicated by the military’s myriad of other difficulties getting new troops in the door, such as recruiting efforts quashed by the pandemic, a shrinking pool of eligible recruits, and social media silos complicating advertising. And amid public scandals, such as the 2020 murder of Vanessa Guillén and suicides on the aircraft carrier USS George Washington, military service may seem like a less attractive choice for young Americans.

“This is arguably the most challenging recruiting year since the inception of the all-volunteer force,” Lt. Gen. David Ottignon, the Marine Corps officer in charge of manpower, told the Senate during a public hearing April 27.

All of the military’s service branches are scrambling to find ways to compete for a younger generation of talent that has plenty of employment opportunities.

“The military provides a wonderful option for young people, but it’s not the only option and so recruiters, I think just like other employers, are trying to understand what the different options are for young people and to address those effectively,” said Joey Von Nessen, an economics professor at the University of South Carolina.

The bonuses that serve as one of the most immediately tangible lures for new recruits, while escalating, aren’t uniform across or even within the services.

Most of the bonuses offered for new Air Force recruits range around $8,000 for certain career fields. But for two of the most dangerous jobs, Special Warfare operations and explosive ordnance disposal, the service is making its maximum allowed offer of $50,000 for people to join.

“It is necessary. I think these are two of our hardest career fields to recruit toward,” said Col. Jason Scott, chief of operations for the Air Force Recruiting Service. “It is absolutely necessary to do $50,000 for each of those, and actually $50,000 is the highest initial enlistment bonus amount that we can give.”

Overall, the Air Force is dedicating $31 million to recruiting bonuses in 2022, nearly double what was originally planned for.

The Army faces the same problem — and is putting up the same big offers.

“We’re in a search for talent just like corporate America and other businesses; almost everyone has the same issue the military does right now,” Maj. Gen. Kevin Vereen, head of U.S. Army Recruiting Command, told Military.com. “We’re trying to match incentives for what resonates. For example, financial incentives. Nobody wants to be in debt, so we’re offering sign-up bonuses at a historic rate.

“We’ve never offered $50,000 to join the Army,” he added.

In addition to the sign-on bonuses, the Army is also offering new recruits their first duty station of choice — an unprecedented move as new soldiers are typically placed at random around the world. New recruits can choose locations such as Alaska, Fort Drum in New York, and Fort Carson in Colorado.

“Youth today want to make their own decisions. We’re letting them do that,” Vereen said.

The services are also trying to keep troops from leaving, knowing that a raft of employment opportunities are available for them if they get fed up with military life.

The Army, Air Force and Navy have all announced reenlistment bonuses for certain career fields and specialties, some of them in the six-figure range.

The Air Force is offering up to $100,000 reenlistment bonuses based on experience and career field. The Navy is also offering those incentives, with fields such as network cryptologists and nuclear technicians making anywhere from $90,000 to $100,000. The Army is offering a more modest cap of $81,000 to reenlist for some jobs.

Anecdotally, military families are describing on social media an inability to find open slots for TAP’s sessions. Each in-person class is generally limited to 50 people, but Lawrence, the Pentagon spokesperson, denied the program is being overwhelmed since classes are also available in live online, on-demand or hybrid formats.

The urgency described by leaders who are putting their money toward keeping skilled service members is a sign of the worry about a brain drain.

Unlike the broader enlistment bonuses, many military career fields don’t offer cash for reenlistment, and some of these incentives existed prior to the pandemic. But the job market has put pressure on the services to pay up to keep service members in the force.

Overweight and Hard to Reach

The military’s difficulties attracting recruits go far beyond making the right bonus offer. The forces working against recruiting increased during the grinding global pandemic — lockdowns kept recruiters home and young Americans are refusing vaccines, for example — and are also rooted in longer-term societal shifts in physical fitness and communication.

“The aggregate effects of two years of COVID is that is two years of not being in high school classrooms, two years of not having air shows and major public events like being in those public spaces, where our potential applicants or potential recruits are getting personal exposure, face-to-face relationships with military recruiters,” Thomas said.

Only about 40% of Americans who are of prime recruiting age are vaccinated against the virus. Outright refusal to get the shot immediately precludes joining the force and short-circuits any pitch from recruiters. COVID vaccines are among at least a dozen inoculations mandated by the Defense Department.

“Seventeen-to-24-year-olds are not getting vaccinated, and those [are] people we aren’t having a conversation with,” Vereen said.

Even when potential recruits are interested and big bonuses motivate them to sign on the dotted line, only about 23% of young Americans are even eligible for service.

Past legal run-ins or a drug history prevent potential recruits from joining, and more and more Americans are overweight. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 40% of adults aged 20 to 39 are obese. That problem has been deemed a national security risk by somebecause it causes an increasingly shallow pool of potential recruits.

The confluence of challenges has others loudly alerting the public that there’s a problem.

Sen. Thom Tillis, R-N.C., the ranking member of the Senate Armed Services Committee personnel panel, says the military is on the cusp of a recruiting crisis.

“To put it bluntly, I am worried we are now in the early days of a long-term threat to the all-volunteer force. [There is] a small and declining number of Americans who are eligible and interested in military service,” Tillis said during an April 27 hearing.

He added that “every single metric tracking the military recruiting environment is going in the wrong direction.” Just 8% of young Americans have seriously considered joining the military, while only 23% are eligible to enlist, according to Tillis.

Meanwhile, the prime demographic for recruiting — 17-to-24-year-olds — is getting harder to reach. The military is running high production value recruiting ads on TV, but most younger Americans are watching YouTube, Twitch and other streaming services. On those platforms, ads are dictated by algorithms based on a person’s search history, and prime-age viewers may never be exposed to recruiting spots if they don’t already have a general interest in the military.

The military has relied on Facebook, with its user base that skews much older, and Instagram pointing users to ads based on their existing interests. The Defense Department banned TikTok from government-issued phones in 2019, shutting out Generation Z’s social media platform of choice. However, some recruiters have ignored the ban on the Chinese-owned platform, which is seen by some as a security risk.

“I know a lot of young people are on TikTok and we’re not,” Vereen said.

When the military does get widespread exposure and makes the news, it can be due to scandals such as the slaying of Guillén at Fort Hood, Texas, or other problems that raise questions about safety and the quality of life in the services.

Following a wave of suicides and disclosure of a lack of basic ameneties such as hot water and ventilation aboard the George Washington, Master Chief Petty Officer Russell Smith, the Navy’s top enlisted leader, was asked by a sailor why the service was spending so much on new recruits, specifically mentioning the hefty $25,000 bonus.

“I gotta use those bonuses to compel something. … A post-COVID workforce doesn’t love the idea that they have to, they actually have to go to work, talk to people, see them face-to-face, exchange ideas and do work,” Smith told the crew, according to a Navy-provided transcript. “They would rather phone it in or work from home somehow and, with the military, you just can’t do that.”

Some sailors said it didn’t seem like the service was prioritizing making its current ranks happy or financially incentivizing them to stick around. Smith said the Navy already offers some bonuses to in-demand specialties and that if a particular job doesn’t offer one it’s because enough of those sailors “love the work that they do … and when they do, I don’t have to use money as leverage.”

Smith also told the sailor that he “can compel [them] to stay right here for eight years.” Most contracts have an inactive period of reserve service built in following the end of active duty that the Navy can tap into.

“So, you want me finding sailors to come in and relieve you on time,” Smith added.

The military services hope the new bonuses will overcome all the difficulties and that they will meet recruiting goals for the year. But the numbers are not encouraging so far.

The Army has an uphill climb for the rest of the year, having recruited just 23% of its target in the first five months of the fiscal year.

The Navy said that, in order to reach its recruiting goal this year, it will have to reduce the delayed-entry program — allowing someone to enlist before they plan on actually shipping out — to below “historic norms,” which could in turn cause recruiting issues in future years.

There’s likely no relief in sight, according to experts.

U.S. population demographics are going in the wrong direction and will make the recruiting job increasingly hard. The millennial and Gen-Z generations are smaller than previous generations, meaning there is a dwindling workforce to pull from. And only a small percentage of those youths appear likely to meet the physical qualifications to join in the first place.

“I think it’s likely that the labor shortage is going to be long-lasting,” Von Nessen said. “This is not a short-term phenomenon. It was exacerbated by the pandemic, but it wasn’t created by the pandemic exclusively.”